How can informal protected areas help China achieve biodiversity goals?

Please find the revised text below:

We encourage you to republish articles from China Dialogue, either in print or online, under the Creative Commons license. Kindly go through our republishing guidelines for a smooth start.

The Langya area off the coast of Shandong province is a hidden gem for marine life, with several rare species calling it home. Among them is the Japanese seahorse, which is under threat from overfishing and habitat destruction. Fortunately, local fishers from the town of Langya are working to protect the area and its unique biodiversity. By creating marine protected areas and implementing sustainable fishing practices, they are helping to ensure that the seahorse and other species can continue to thrive for years to come. These efforts are not only important for the health of the local ecosystem but also for the livelihoods of the fishers who depend on the sea for their income. It’s inspiring to see individuals and communities taking action to protect our oceans and the creatures that inhabit them.

The given text consists of two dates, “October 6, 2022” and “November 17, 2022”.

The Yellow Sea’s species-rich region near Qingdao is where the township of Langya is located. This area is the habitat for various rare and protected animals, including the Japanese seahorse and the narrow-ridged finless porpoise.

The small yellow-brown Japanese seahorse, which lives in shallow water coral reefs and seagrass meadows, can easily be missed in a haul of fish. Its population is threatened by habitat loss and bottom trawling. Due to these factors, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has listed it as vulnerable. Local fisher Liu Shujie stated that initially, the IUCN experts did not believe there were still seahorses in the area. They were amazed to see that a fishing net had caught 138 seahorses in just 10 minutes.

China’s seahorse populations have been threatened by habitat loss and overfishing, prompting the country to take action to protect these species. In 2021, all 14 species of seahorses found in Chinese waters were given Class II protections. However, prior to this, seahorse populations in certain areas were not given specific protections.

One such area is the habitat of the Japanese seahorse, which was identified by IUCN seahorse experts in 2017. This area is home to several rare and protected species, including the narrow-ridged finless porpoise. Despite its importance, no special protections were put in place until local fisher Liu Shujie took the lead.

In 2019, Liu and other fishers formed the Blue Bay Centre, a conservation group aimed at protecting the area. They patrol the waters in their boats to prevent bottom trawling and other destructive fishing practices. Their efforts have been successful in protecting the Japanese seahorse population and other species living in the area.

The Japanese seahorse is a small yellow-brown creature that lives in shallow water coral reefs and seagrass meadows. It is threatened by habitat loss and overfishing, and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists it as vulnerable. In fact, IUCN experts were surprised to find that there were still seahorses living in the area when Liu and his group brought 138 of them up in only 10 minutes using a fishing net.

The efforts of Liu and the Blue Bay Centre highlight the importance of community-based conservation efforts in protecting vulnerable species and their habitats. Through their work, they have shown that even small-scale actions can have a significant impact on protecting biodiversity.

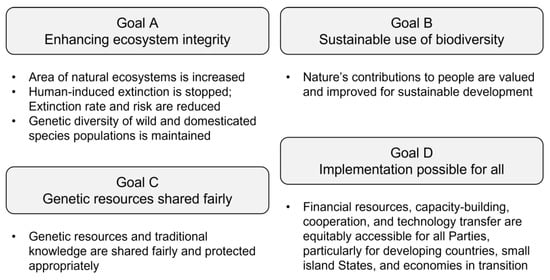

The success of the Blue Bay Centre’s conservation efforts could contribute to the Convention on Biological Diversity’s goal of having 30% of the world’s land and ocean area protected by 2030, through the use of Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures (OECMs). The upcoming CBD talks later this year aim to reach an agreement on this “Thirty by Thirty” target. However, China currently lacks a system for identifying and managing OECMs, which means that there is still much work to be done to determine whether OECM definitions are being met.

Community-protected areas, at sea

The members of the Blue Bay Centre are fishers from a village with a rich history of fishing. The locals have a deep connection to the ocean and their fishing skills are passed down through the generations. Liu Shujie, in particular, is known for his persuasive abilities. When he learned about fishers in other countries getting involved in conservation efforts, he used his influence and popularity, along with support from a charity, to rally the local fishers and form the Blue Bay Centre.

Liu Shujie, a fisherman, established the Blue Bay Centre to safeguard the rich marine habitats that his community has relied on for several generations. (Image credits: Qingdao Marine Conservation Society)

More than 20 captains of small boats have joined Liu Shujie’s team of “blue bay guardians.” Although they have no legal authority, the local marine development bureau has authorized them to discourage offenders and file reports. The members take breaks from their workday to monitor the region they safeguard and try to persuade boats using harmful practices like bottom trawling to leave. They also report any incidents of waste disposal or other harmful actions.

The Blue Bay Centre, a group of fishers from the village of Langya in Shandong province, has been working tirelessly to protect the waters that are home to several rare and protected animals, including the Japanese seahorse. This small yellow-brown creature is threatened by bottom trawling and habitat loss, and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists it as vulnerable.

Led by Liu Shujie, the Blue Bay Centre has over 20 small vessels patrolling the area they protect to dissuade offenders and make reports of any instances of waste dumping or other harmful actions. While they have no law-enforcement powers, the local marine development bureau has empowered them to carry out their work.

The group’s patrols and publicity work have raised awareness among local fishers about the importance of protecting seahorses. This is in stark contrast to the practice of catching and even openly selling seahorses seen elsewhere. Liu cites a case involving a seahorse stall at the nearby Rizhao market, which saw over 20 fishers arrested.

If the group’s conservation work meets the Convention on Biological Diversity’s definition of Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures (OECM), it could count towards the target of having 30% of the world’s land and ocean area protected by 2030. The hope is that an agreement will be reached on this “Thirty by Thirty” target at the CBD talks later this year. However, China has no system for identifying or managing OECMs, and there is much work to be done before the country can confirm if and where OECM definitions are being met.

The Blue Bay Centre’s work is not only crucial for protecting rare and threatened species, but it also shows the power of community-led conservation efforts. With their deep connection to the ocean and their long tradition of fishing, the villagers of Langya are in a unique position to ensure the sustainability of their local waters.

According to Liu Yi, who is the national coordinator of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), they are providing support to the fishers of Langya to improve their local capacity, build a sense of pride in conservation work, and preserve resources for future generations through charitable projects, as they have shown enthusiasm for protecting the area. The group is also encouraged to communicate and cooperate with the local authorities and gain government recognition.

Liu states that unlike the formally established protected areas, the UNDP aims to encourage the establishment of community-protected areas that do not need to be completely closed off and can still be used sustainably while maintaining traditional fishing practices in the area. The Qingdao Marine Conservation Society is assisting in empowering groups such as the Blue Bay Centre with the support of the UNDP.

Creating community-protected areas at sea is a challenging task due to the lack of well-defined laws governing ocean use by traditional fishers. Unlike protected areas on land, where various forms of land use are regulated through a permit system, there are no clear rules to distinguish between commercial and artisanal fishing. This has resulted in traditional fishers having a “quasi-legal” right to use the sea.

According to Liu, community-protected areas should be established by local residents and managed through mutual agreement without any government approval or financial support. However, receiving official recognition can provide legal support and place the areas on a more formal footing. For instance, in 2011, the EU-China Biodiversity Programme by the UNDP provided assistance, and Guangxi province formulated regulations for the community management of forest and wildlife reserves. This enabled community-managed reserves to register with the forestry authorities and gain government recognition.

The Blue Bay Centre’s protected ocean area is being considered for recognition as an OECM.

Potential OECMs

Although the concept of OECMs is not new and was already included in the Aichi biodiversity targets in 2010, it was not until 2018 that a CBD conference established a clear definition. In 2019, guidelines were published on recognizing and reporting on OECMs, along with a database of such areas. This development made it possible to include OECMs when tracking progress towards the Aichi targets.

The definition of OECMs, according to CBD, is “a geographically defined area other than a protected area, which is governed and managed in ways that achieve positive and sustained long-term outcomes for the in situ conservation of biodiversity, with associated ecosystem functions and services.” While there are some differences in terms of definition, starting point, and aims between OECMs and community-protected areas, community-protected areas are generally considered a type of OECM worldwide.

The Qingdao Marine Conservation Society is working towards protecting the waters of China’s Blue Bay through community-led conservation efforts. One of the group’s initiatives involves encouraging local fishers to establish community-protected areas that can help preserve the region’s biodiversity while allowing for sustainable fishing practices.

Unlike officially established protected areas, community-protected areas are not necessarily sealed off and can still be used sustainably, without affecting the traditional fishing practices in the area. However, setting up such areas can be difficult, particularly as laws on ocean use by traditional fishers are not well-defined, and there are no clear rules distinguishing between commercial and artisanal fishing. This has left traditional fishers with a “quasi-legal” right to use the sea, making it challenging to establish community-protected areas.

To address this challenge, the UNDP is supporting initiatives to enhance local capacities, build a sense of pride and recognition for conservation work among fishers, and preserve resources for future generations through charitable projects. The goal is to empower local residents to form community-protected areas spontaneously, managed by local consensus, without government approval or financial backing. However, official recognition can provide legal support and put the areas on a more formal footing.

The Blue Bay Centre is an example of a community-led conservation initiative, where fishers have come together to protect the species-rich waters that their community has relied on for generations. The centre has over 20 small vessels captained by “blue bay guardians” who patrol the area, report harmful actions and try to persuade vessels to leave if they employ destructive techniques like bottom trawling.

Community-led conservation efforts like those of the Blue Bay Centre and the UNDP’s initiatives to support community-protected areas and Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures (OECMs) are essential for the protection of marine biodiversity. With the establishment of community-protected areas, there is hope that the area of ocean protected by the Blue Bay Centre will be recognised as an OECM.

Wang Songlin, the president of the Qingdao Marine Conservation Society, stated that community-protected areas prioritize the interests of local communities and indigenous populations, who are responsible for leading conservation efforts. He further explained that his organization has been collaborating with the Blue Bay Centre since 2021 to find ways to protect the nearby coastal biodiversity while also promoting the local economy through small-scale artisanal fishing. Funding for this project has been provided by the UNDP and the Zhilan Foundation. Success in this endeavor would be a significant example of a marine OECM in China.

Setting up protected areas in traditional coastal fishing grounds that include strict bans on human activity in core areas faces strong political resistance. Local fishing communities and governments at all levels are not in favor of such constraints on the various ways those waters are used. However, there is a huge potential for community-managed marine areas known as OECMs. According to Wang Songlin, president of the Qingdao Marine Conservation Society, these areas would increase consensus among various stakeholders on marine biodiversity conservation and the stewardship of fishery resources and make joint efforts possible.

The UNDP and the Zhilan Foundation have been funding the society’s work to explore ways to protect coastal biodiversity while developing the local economy through small-scale artisanal fishing. This approach aligns with the concept of OECMs, which Wang believes will be a valuable example of Chinese marine conservation. Liu Yi, national coordinator with the UNDP, thinks that OECMs will be more diverse in terms of who runs things, the methods used, and the sources of funding. They may even be more cost-effective while achieving better outcomes compared to traditional protected areas.

China is a country with a diverse range of ecosystems and habitats that are home to a rich variety of plant and animal species. However, like many other countries around the world, China faces a number of challenges when it comes to conserving biodiversity. One approach that could help in this regard is the establishment of Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures (OECMs).

OECMs are geographically defined areas other than protected areas that are managed in ways that promote positive outcomes for the conservation of biodiversity and associated ecosystem functions and services. While there are differences between OECMs and traditional protected areas in terms of their governance and management, both are important tools for conserving biodiversity.

In China, setting up formal reserves in traditional coastal fishing grounds has been met with political resistance. This is because local fishing communities object, and governments do not want to see constraints on the various ways those waters are used. However, there is huge potential for OECMs managed by local artisan fishers. These would increase consensus among various stakeholders on marine biodiversity conservation and the stewardship of fishery resources, and make joint efforts possible.

The establishment of OECMs in China could have significant benefits for the country’s goals on biodiversity conservation. By increasing the involvement of local communities in the management of protected areas, OECMs can promote a sense of ownership and stewardship among these communities, leading to more effective conservation outcomes. In addition, OECMs can help to address gaps in the protection of biodiversity that may exist outside of traditional protected areas, providing additional safeguards for threatened species and ecosystems.

Overall, the establishment of OECMs in China represents an important opportunity to promote biodiversity conservation and sustainable development in the country. By working with local communities and stakeholders, China can develop effective and inclusive approaches to conservation that benefit both people and nature.

The upcoming COP15 meeting of the Convention on Biological Diversity is set to take place in Montreal later this year. The post-2020 global biodiversity framework draft presented at the conference proposed a target to protect 30% of both land and sea areas by 2030. However, it is unlikely that formal reserves alone would be able to achieve this ambitious “Thirty by Thirty” target. To this end, Lü Zhi, founder of the Shanshui Conservation Centre and professor at Peking University’s School of Life Sciences and Institute of Ecology, has advocated for the need to establish a system for certifying and supporting OECMs in China as a means of achieving this goal.

As of the end of 2019, China had established 271 marine protected areas, covering 124,000 square kilometres, which amounts to 4.1% of its total jurisdictional waters. This falls short of the global average of 7.92% in 2021, as well as the 11th Aichi Target, which aims to protect 10% of coastal and marine areas.

Liu Yi suggests that China can implement the Convention on Biological Diversity by offering policy, legislative, financial, and technical support to in-situ conservation efforts like those carried out by the Blue Bay Centre and recognizing the protected area as an OECM.

How far to true OECMs?

The effective management of the sea area patrolled by the centre requires the support mentioned above, according to Liu Yi.

Liu Shujie mentioned that funding is a major challenge. He explained that a single patrol takes at least an hour, which costs around 350 yuan (US$50) in terms of fuel and labor expenses. Additionally, more time is spent on documenting patrol logs, recording what was discovered, and how it was managed. He stated that they have accumulated two large stacks of patrol logs so far, and they have dealt with nearly 1,000 vessels. Despite receiving some funding from Chinese NGOs, it is insufficient to cover their expenses.

The Qingdao Marine Conservation Society, a non-governmental organization that works to protect marine biodiversity in China, faces several challenges in its efforts to safeguard the waters it patrols. One of the key challenges is funding, as each patrol can cost around 350 yuan (US$50) in fuel and labor costs, which adds up quickly over time. Despite receiving some funding from Chinese NGOs, the organization struggles to cover all its expenses, including the cost of maintaining a formal office.

According to Liu Shujie, a member of the society, the organization has dealt with around 1,000 vessels so far and has two piles of patrol logs to show for it. He explains that a patrol takes at least an hour and that more time is spent filling in logs and recording the results of each patrol. The organization needs a more stable source of funding to be able to continue its work effectively and make a real difference in the conservation of marine biodiversity in China.

The organization would also like to have an office, which would give it a more formal presence and help it in its efforts to secure government funding. However, it currently lacks the funds to rent an office space, which is a major obstacle in its efforts to expand its operations and make a greater impact.

Despite these challenges, the Qingdao Marine Conservation Society remains committed to its mission of protecting China’s coastal waters and marine life. With more support from the government and other sources of funding, the organization could expand its operations and have an even greater impact on the conservation of China’s marine biodiversity.

The Blue Bay Centre, a voluntary marine conservation effort in China, faces significant challenges despite its commendable efforts to protect the sea area it patrols. According to Wang Songlin, the centre still lacks legal status and policy backing, which makes it difficult to manage the protected area effectively. The Blue Bay Centre focuses on an area that is also a significant source of livelihood for local fishing communities, and different types of fishing activities pose varying threats to both protected and commercially fished species.

While the efforts of the Blue Bay Centre are commendable, there is still a pressing need for more scientific and sustainable management of the area. Such management would require support from policymakers, governmental organizations, and the scientific community. The centre has a crucial role to play in promoting awareness of the importance of marine conservation and encouraging cooperation among various stakeholders in the area.

The lack of legal status and policy backing also affects the centre’s ability to secure funding for its operations. Without adequate funding, it is difficult to sustain the centre’s efforts to patrol the area and enforce marine conservation regulations effectively. This lack of funding also prevents the centre from establishing an office to formalize its operations.

In conclusion, while the Blue Bay Centre’s efforts are admirable, more needs to be done to support its work. This includes providing legal status and policy backing, ensuring scientific and sustainable management of the protected area, and securing funding to sustain the centre’s operations. Achieving these goals will require cooperation among various stakeholders and a commitment to marine conservation.

The Qingdao Marine Conservation Society is collaborating with charitable and academic institutions to assist the Blue Bay Centre in determining the borders of the protected area, enhancing the patrols’ data-gathering and quality, and seeking legal and regulatory assistance for community-protected OECMs. The society is also exploring the feasibility of selective fishing techniques and strategies to minimize damage to the seabed, endangered species, juvenile fish, and smaller fish populations. These practical approaches, based on science, technology, and policy, will assist governments at all levels in better directing the delineation, management, and expansion of marine OECMs.

An OECM system of China’s own

China will require a system to be in place for recognising community-protected areas like this one or any other as an OECM.

China faces unique challenges in implementing OECMs, and there is still much work to be done to establish guidelines, incentives, and databases for identifying and managing these areas. According to a paper published earlier this year by The Nature Conservancy’s China Program, Chinese researchers have only recently begun to consider this issue, and there is disagreement among experts on which areas should be recognized as OECMs. Moreover, existing guidance documents for OECMs are based on examples from North America and Europe, which may not be directly applicable to China’s context.

To effectively implement OECMs, the paper calls for the establishment of guidelines for assessing, identifying, and managing these areas that are tailored to China’s unique circumstances. This will require extensive collaboration between local communities, governments, and conservation organizations to identify areas that have high biodiversity value and are threatened by human activities. It will also require the creation of incentives and support mechanisms for local communities to manage and protect these areas.

One crucial step will be the creation of a database to track and monitor OECMs, which will require significant investment in technology and infrastructure. This database will be an essential tool for measuring progress toward China’s conservation goals and identifying areas that require additional protection.

Overall, the establishment of OECMs has the potential to be a powerful tool for protecting China’s rich biodiversity while also supporting the livelihoods of local communities. However, much work remains to be done to establish the necessary guidelines, incentives, and databases to support this effort.

Liu Yi and other experts believe that China has a plethora of land and sea areas that are appropriate for OECMs. Liu Yi has suggested that OECMs could include community-protected areas, ecological forest areas, water source protection areas, natural forest protection projects, ecological redline zones, and even rewilded urban green areas and wetlands. Jin Tong and Lü Zhi have made similar recommendations in their papers. Although there is already a solid basis for OECMs in China, they still need official recognition, along with policy and financial backing, according to Lü Zhi.

Liu Yi explained that the biggest challenge in monitoring and assessing potential OECMs is ensuring long-term and effective conservation. She suggests that the government could involve third-party organizations, such as research bodies, to provide capacity building for NGOs and local communities. This would enable NGOs to help communities carry out in-situ monitoring and long-term data gathering needed for evaluation. Liu Yi hopes that the government will lead or support an OECM fund, providing long-term financial and technical support and incentives. She also suggests setting up a database of OECMs, a regular evaluation mechanism, and making findings public. Additionally, Liu Yi calls for strengthening public oversight of OECMs and taking action when OECMs fail to meet standards, either by requiring improvements or removing the designation.

China was one of the first countries to sign the Convention on Biological Diversity, and it is crucial for the country to recognize and support the identification of OECMs. Liu Yi, a researcher in the field of conservation, believes that it is essential for China to include OECMs within its system of protected areas, not only to implement the convention but also for its own needs. However, Liu Yi points out that the inclusion of OECMs in the system of protected areas does not necessarily mean that they will become state-protected areas. Instead, it means using policy and regulation to empower those running OECMs to protect and manage the area, particularly the existing community-protected areas overseen by local communities, such as sacred mountains, lakes, and “fengshui forests.” This would help formalize protection and put it on a legal footing.

Liu Yi suggests that the Chinese government should provide policy, legislative, financial, and technical support for in-situ conservation such as that practiced by community-protected areas. She also stresses the importance of recognizing the protected area as an OECM, which would help China implement the Convention on Biological Diversity. However, Liu Yi acknowledges that monitoring and assessing potential OECMs in the long term is a significant challenge. She suggests that the government could work with research bodies to provide capacity building for NGOs and local communities. NGOs could then help those communities carry out in-situ monitoring and long-term data gathering needed for evaluation.

In conclusion, recognizing and supporting the identification of OECMs is crucial for China’s conservation efforts. While China has a good foundation for OECMs, they need to be officially recognized with policy and financial support. Liu Yi believes that including OECMs within the system of protected areas would formalize protection and put it on a legal footing, particularly for existing community-protected areas overseen by local communities.